Show summary Hide summary

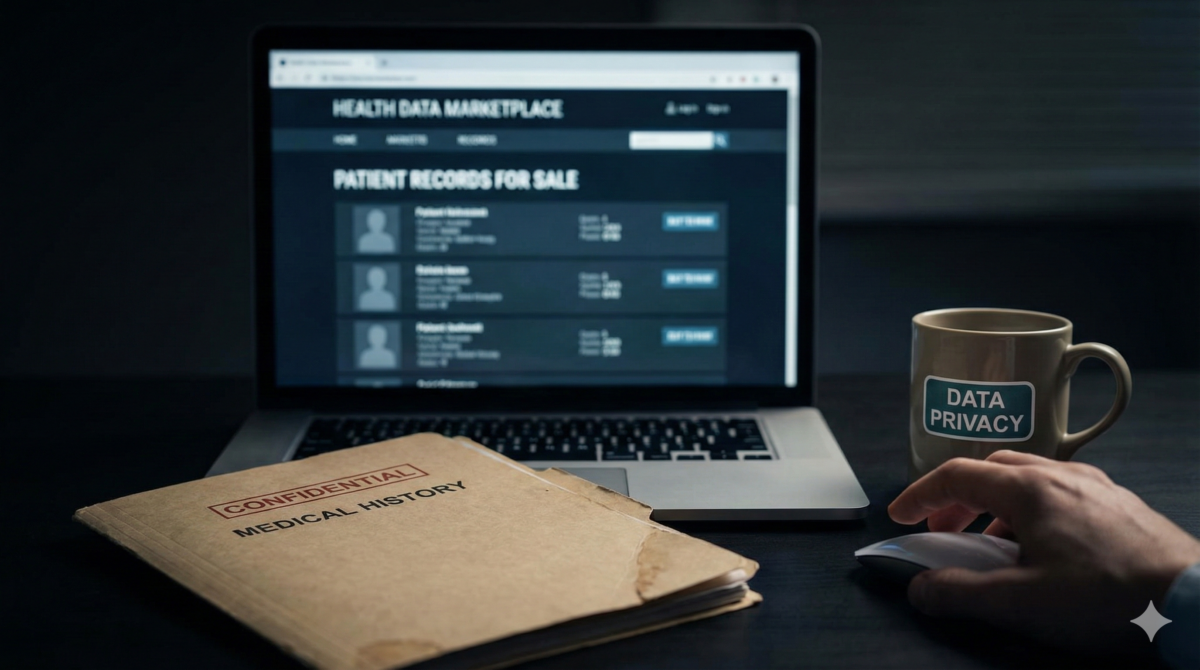

That moment you realise your health life is for sale

I was skimming yet another privacy update when one detail stopped me cold. A marketing firm had quietly traded the health data of millions of people. There was no obvious scam email, no strange URL, just a dry regulator announcement that suddenly felt very personal.

The California Privacy Protection Agency explained that a company called Datamasters had packaged and sold detailed health and personal information. All of this happened without the company being registered as a legal data broker. As a result, the entire platform operation existed in a legal grey zone.

At first, I wondered if this was just another routine enforcement action. Then the scale sank in. Millions of profiles, mapped to health interests and likely conditions, had been sliced into neat marketing segments. That is exactly the kind of quiet scam territory that criminals and shady brokers prefer.

Hacker forum implodes and leaks its own secrets. Why your private data may be next

Microsoft Just added a ‘kill switch’ for Copilot. What are they afraid admins will discover?

After reading that, I went back to my inbox and the ads on my screen. I checked which health newsletters I had joined and which surveys I had filled out. I even grabbed a quick screenshot of a hyper-targeted supplement ad, just in case. It felt like a tiny piece of proof of how far this profiling can go.

This kind of case is not your classic phishing link, though. It is more subtle. Your data moves in the background, while you only see the final ad or offer. So let me walk you through the signals of this hidden data trade and the practical verification steps you can actually take.

The signs your health data is quietly monetised, explained clearly

- Hyper-specific health ads that follow you across multiple sites after a single search or form submission are a strong red flag.

- Emails about conditions you never discussed with your doctor, but may have clicked on in a quiz, often reveal silent data resale.

- Marketing messages that combine your age group with a very specific symptom usually indicate purchased profiles.

- A missing or vague privacy notice, or no mention of broker registration on a health survey site, should raise suspicion.

- Very long consent text that bundles “research,” “marketing,” and “partner sharing” typically hides broad data use.

- Opt-out links that send you to generic pages with no working URL for real choices deserve serious distrust.

- Health discount offers arriving right after you use a symptom checker strongly suggest background sharing of your data.

- Repeated emails asking you to “confirm” your medical interests often signal quiet profiling updates in their database.

- Any request for medical details paired with contests, giveaways, or gift cards is a major red flag.

- Sites that demand health information before showing their privacy policy should immediately worry you.

The checks that expose hidden brokers before your data spreads

- Step 1. In the first five minutes, scan the site footer for a privacy policy and any mention of a data broker or sharing partners. If there is no clear policy, treat that as a warning sign. Legitimate firms usually display this information upfront.

- Step 2. Before you enter symptoms, copy the site’s domain and search it together with the words “broker” or “complaint.” Spend two or three minutes on this. You may uncover regulatory actions or user reports that reveal how your data is being traded.

- Step 3. When a consent box pops up, take a minute to read the lines about partners, advertisers, and analytics. If it says your health interests may be shared with unnamed parties, capture a quick screenshot as later proof.

- Step 4. If you receive a new health marketing email, check the full sender address and any tracking URL. In two minutes, you can look for references to list providers or data partners, which often show that your profile was purchased.

- Step 5. Once a month, download or review your ad settings on major platforms and look at the health interests listed there. Spend about ten minutes. Remove any category you never knowingly provided. This limits how far past data sales can keep following you.

- Step 6. If you live in California, search the state data broker registry by company name. This takes only a few minutes and shows who officially trades consumer information under state law.

- Step 7. When a site offers free health tests, pause for five minutes and search its name plus “privacy” or “fine.” You might uncover enforcement actions similar to the Datamasters case, which signal risky sharing practices.

- Step 8. Keep a simple note of which health sites you use and when new targeted ads start appearing. After a week or two, patterns will emerge and help you identify the likely source of the data flow.

What to do now if your health data may be out there

If you clicked on a suspicious health ad or quiz, close the tab and clear cookies for that specific domain. Then open your browser settings and disable third-party tracking where possible. This will not erase existing data, but it will slow down new collection.

If you shared medical details, log back into that platform. Change your password, tighten privacy options, and delete the profile if you can. After that, update your email security settings, because health data combined with contact details is extremely valuable to scammers.

If you paid for tests or supplements after seeing targeted ads, contact your bank or card provider quickly. Ask about chargeback options and monitor your statements closely. Keep every email, invoice, and screenshot as proof, since timing often decides your chances of a refund.

For reporting, if you are in California, you can alert the California Privacy Protection Agency. Across the United States, you can also submit a complaint to the Federal Trade Commission. It may feel formal and distant, yet each report helps regulators spot broader patterns.

The reflex to keep when facing quiet data grabs

The core reflex is simple. Before you share any health detail online, assume someone may try to turn it into a profile for sale. Then, intentionally look for the privacy trail and any obvious red flag. There is no need for panic, just a brief, deliberate pause.

In the Datamasters story, the loudest clue was the missing broker registration even as millions of records were being sold. That gap between massive scale and thin transparency is telling. When a firm hides its real role, your data is rarely safe.

Sometimes the site will be a harmless newsletter with clumsy wording. Other times it will be a polished symptom checker bankrolled by aggressive marketing buyers. The surface can look almost identical, which is exactly why those extra checks matter so much.

If this made you rethink even one health quiz or ad in your inbox, pass the warning on. The more people recognise these quiet red flag patterns, the harder it becomes for hidden brokers and shady platform operators to trade your health life in the dark.

FAQ

What happened in the Datamasters case?

Datamasters packaged and sold detailed health and personal information about millions of people without being registered as a legal data broker, operating in a legal grey zone until regulators intervened.

What are common signs that my health data is being quietly monetized?

Red flags include hyper-specific health ads that follow you across sites, emails about conditions you only clicked on in quizzes, vague or missing privacy notices, bundled consent for “research,” “marketing,” and “partner sharing,” and health-related contests asking for medical details.

How can I quickly check if a health site might be sharing my data with brokers?

Look for a clear privacy policy and any mention of data brokers or partners in the footer, search the domain with words like “broker,” “complaint,” or “fine,” and read consent pop-ups for references to sharing health interests with unnamed advertisers or partners.

What should I do if I suspect my health data has already been misused?

This terrifying US stalkerware case just exposed a global surveillance nightmare

Big tech just turned on you : why your favorite platforms are about to become your biggest threat

Clear cookies for the suspicious site, disable third-party tracking in your browser, tighten or delete your account on that platform, strengthen your email security, and if you made purchases, contact your bank or card provider and keep all related records.

How can I monitor and limit ongoing health profiling in ads?

Regularly review and adjust ad settings on major platforms to remove unwanted health-interest categories, track when new targeted health ads appear relative to sites you visit, and treat any new, highly specific health marketing as a cue to recheck your privacy choices.

Glossary

- Health data. Personal information related to an individual’s physical or mental health, symptoms, conditions, treatments, or health-related behaviors. In this context, it includes data inferred from searches, quizzes, symptom checkers, and health newsletters.

- Privacy policy. A document or webpage explaining how a company collects, uses, shares, and stores personal data. It should clearly state whether health information is sold, shared with partners, or used for targeted advertising.

- Data broker. A company that collects, aggregates, and sells or shares personal data—often from many sources—to other organizations for marketing, profiling, or analytics, usually without having a direct relationship with the individuals concerned.

- Targeted marketing. Advertising that uses personal or inferred data—such as age, health interests, or likely medical conditions—to deliver highly specific ads or offers to particular individuals or groups across websites, apps, or email.

- Profiling. The process of analyzing and combining data about a person to infer characteristics, interests, or likely behaviors, such as possible health conditions, and then placing them into segments used for marketing or other decisions.